General information only; not personal medical advice. Decisions about ICSI should follow a male‑factor evaluation and your clinic’s guidance.

Featured answer

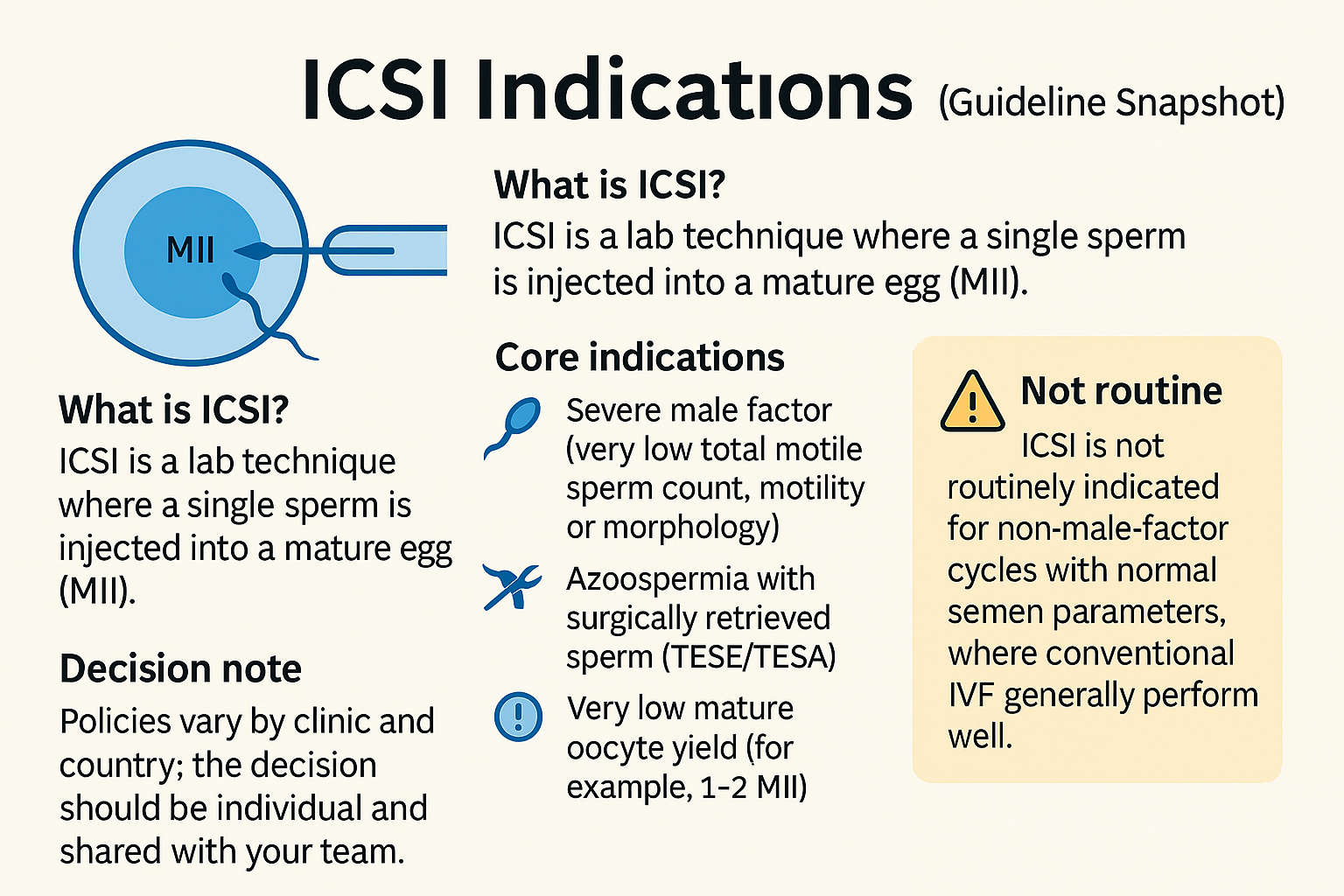

ICSI is a lab technique where a single sperm is injected into a mature egg (MII). Most guidelines list core ICSI indications as: severe male factor (very low total motile sperm count, motility or morphology), azoospermia with surgically retrieved sperm (TESE/TESA), prior total fertilisation failure or very low fertilisation, and very low mature oocyte yield (for example, 1–2 MII). ICSI is not routinely indicated for non‑male‑factor cycles with normal semen parameters, where conventional IVF generally performs well. Policies vary by clinic and country; the decision should be individual and shared with your team.

FEATURED SNIPPET (Direct Answer)

ICSI is usually indicated for severe male factor, surgical sperm retrieval, prior total fertilisation failure, or very low mature oocyte numbers. It is not routinely used for non‑male‑factor infertility with normal semen when conventional IVF performs well. Follow your clinic’s evaluation and guidance.

Introduction

You may hear, “we’ll just do ICSI.” It sounds simple, but it changes the lab plan, cost, and consent. This guide explains ICSI indications in plain English and why guidelines caution against routine use in non‑male‑factor cycles.

We compare ICSI with conventional IVF, translate semen analysis numbers, list risks and downsides, and show what ASRM/AUA and ESHRE actually say. Use this as a calm, global decision aid.

ICSI vs Conventional IVF—What’s the Difference?

Simple definition and lab steps (MII oocytes only)

Conventional IVF places many motile sperm with each egg. With ICSI, the embryologist selects one sperm and injects it into a mature (MII) oocyte. Only MII oocytes can be injected.

Fertilisation expectations and lab variation

Both methods aim for normal 2PN fertilisation. Lab fertilisation rates vary with sperm quality, oocyte maturity, and technique. A normal outcome is not guaranteed with either approach.

Common mistake: assuming ICSI always increases live birth

ICSI can reduce fertilisation failure in clear male factor. In non‑male‑factor cycles with normal semen, major reviews do not show improved live birth over IVF.

Evidence: ASRM Committee Opinion on non‑male‑factor ICSI (2020) and ESHRE lab guidance (2021) note no routine benefit in non‑male‑factor cycles.

ICSI Indications (What Most Guidelines Support)

Severe male factor (contextual ranges; avoid rigid cut‑offs)

Clinics often consider ICSI when total motile sperm count is very low or motility/morphology are severely impaired. Thresholds are contextual, not absolute. Prior cycle history and lab performance matter.

Azoospermia with surgical sperm (TESE/TESA/micro‑TESE)

When sperm are obtained surgically, ICSI is typically used because counts and motility are limited.

Prior total fertilisation failure or very low fertilisation

If a prior cycle had 0% or very low fertilisation with IVF, ICSI is a common, guideline‑supported next step.

Very low mature oocyte number (e.g., 1–2 MII)

With very few MII oocytes, clinics may choose ICSI to reduce the chance of total fertilisation failure.

Special cases: antisperm antibodies; prior IVF with suspected mechanical issues

Some labs consider ICSI if antibodies are suspected or prior insemination mechanics seemed to fail.

Evidence: AUA/ASRM Male Infertility Guideline (2021) and ASRM non‑male‑factor ICSI Opinion (2020) list male‑factor and surgical sperm as primary indications.

Non‑Male‑Factor ICSI—When It’s Not Routine

Unexplained infertility with normal semen

Guidelines caution against default ICSI here. Conventional IVF generally achieves good fertilisation.

Endometriosis, tubal factor, donor sperm

These are not in themselves reasons for routine ICSI if semen is normal and lab fertilisation rates are strong.

PGT‑A and ICSI

Some labs prefer ICSI to limit polyspermy or potential contamination. Guidelines note PGT‑A does not mandate ICSI in non‑male‑factor couples. Local lab policy may differ.

Evidence: ASRM Committee Opinion (2020) advises against routine ICSI in non‑male‑factor cycles; ESHRE (2021) echoes caution.

Semen Numbers in Plain English

Understanding TMSC and why labs care

Total motile sperm count combines volume, concentration, and motility. Very low TMSC can reduce IVF fertilisation and support choosing ICSI.

Morphology (strict) and its limits as a predictor

Very low strict morphology may push toward ICSI, but morphology alone is an imperfect predictor. Repeat testing is often useful.

When a repeat semen analysis or male factor work‑up is smarter

Borderline results deserve a second test and andrology/urology input before committing to ICSI.

Evidence: AUA/ASRM (2021) recommends at least two semen analyses in evaluation and targeted work‑up before treatment decisions.

Risks, Downsides, and Unknowns

Oocyte injury risk; failed fertilisation can still occur

ICSI involves piercing the oolemma. Eggs can be damaged, and fertilisation is not guaranteed.

Perinatal risks signal

Large studies suggest small increases in certain outcomes with ICSI/ART overall. The absolute risks are small. Causation is complex and debated.

Cost, time, and opportunity cost

ICSI adds cost and steps. Use it where benefit is likely.

What ASRM/AUA and ESHRE Say

High‑level consensus on indications

Supported: severe male factor, surgical sperm, prior total fertilisation failure, very low MII count.

Non‑male‑factor caution

Do not use ICSI routinely in non‑male‑factor cycles with normal semen parameters.

Shared decision‑making

Explain rationale, alternatives, and local lab performance. Document the indication.

Evidence: ASRM Committee Opinion on non‑male‑factor ICSI (2020); AUA/ASRM Male Infertility Guideline (2021); ESHRE ART lab guidance (2021).

Shared Decision Checklist

7 questions to ask your clinic

- What are our semen analysis numbers (TMSC, motility, morphology)?

- What was fertilisation in any prior cycle?

- What is your lab’s IVF vs ICSI fertilisation rate in cases like ours?

- What is the clear ICSI indication for us?

- Are there alternatives (repeat semen test, male factor work‑up)?

- Does PGT‑A require ICSI at your lab—and why?

- What are the added costs and risks?

Documenting rationale in your plan

Write the indication in the consent (e.g., severe male factor; prior TFF; 1–2 MII).

When to seek andrology/urology input

Abnormal semen or azoospermia warrants specialist input and possible retrieval planning.

Comment: Did your clinic suggest ICSI—what was the reason given (numbers, history, lab policy)? Share to help others.

PROOF & PRACTICALS

Mini case snapshot

Couple A had 0% fertilisation with IVF despite adequate eggs. Next cycle used ICSI and achieved normal fertilisation. Couple B had non‑male‑factor and normal semen; IVF alone gave good fertilisation and pregnancy.

ICSI vs Conventional IVF at a Glance

| When | Why | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Severe male factor | Raise fertilisation odds | Contextual thresholds; repeat testing |

| Surgical sperm (TESE/TESA) | Limited motility/number | ICSI typical |

| Prior total FF | Reduce repeat TFF | Discuss lab performance |

| 1–2 MII oocytes | Avoid total FF | Team preference varies |

| Non‑male‑factor + normal semen | IVF often sufficient | ICSI not routine |

Checklist: Before agreeing to ICSI

- Confirm numbers: TMSC, motility, morphology.

- Review any prior fertilisation outcomes.

- Ask for your lab’s IVF vs ICSI results for similar cases.

- Write the indication into the consent.

- Discuss PGT‑A workflow if relevant.

- Note added cost and small risks.

- Consider an andrology/urology review if needed.

Male factor work‑up basics

History, exam, at least two semen analyses, and targeted tests. Learn more in: Male factor work‑up and What is ICSI?.

FAQ

When is ICSI clearly indicated?

What semen analysis numbers suggest ICSI?

Is ICSI necessary for PGT‑A?

Does ICSI improve success in non‑male‑factor cycles?

What are the risks of ICSI to eggs or babies?

If I had fertilisation failure before, should I do ICSI next time?

Do surgical sperm retrievals always require ICSI?

Conclusion

ICSI indications are clearest in severe male factor, surgical sperm, prior total fertilisation failure, and very low MII numbers. In non‑male‑factor cycles with normal semen, conventional IVF often suffices. Use evaluation‑first, guideline‑aligned decisions and share the rationale in your plan.

Sources

-

ASRM: ICSI for non-male-factor indications (2020) — Committee Opinion on when (and when not) to use ICSI outside male-factor cases.

-

AUA/ASRM Male Infertility Guideline — Part II: Management (2021) — Management guidance (therapy, surgery, ART use). (Direct Part II PDF if needed:) JU article PDF.

-

ESHRE: ART laboratory good-practice recommendations (key docs, 2016–2021) — Guidelines hub • ART lab performance indicators (Vienna Consensus) • Ultrasound practice in ART (oocyte retrieval, etc.).

-

Reviews of ICSI outcomes in non-male-factor cohorts (2018–2022) — examples: Systematic review & meta-analysis (2022, Frontiers) • BMC Women’s Health (2022).

Reminder: ICSI decisions should follow a male‑factor evaluation and clinic guidance. Ask about alternatives and rationale.